13th – 29th April, Tuesday – Saturday, 12 – 6pm

Private view 12th April, 6.30 – 8.30pm

For centuries, the breakup has been the prerogative of men. In the 19th century, the concept of romantic love emerged as the basis for marriage and changed the game. Back in the days of arranged unions, if things didn’t work out, one could blame society. But since the conceptual evolution of the marriage towards sentimental vision, the breakup becomes an attack on the inner self.

Today, about half of all marriages in Europe end in divorce and, significantly, 75 percent of divorce applications are filed by woman. Perhaps that last statistic explains why women suffer more emotional hurt and find it harder than their ex-partners to build a new lifestyle and relationships. The cruel logic would be that if the woman marries for love and then decides it was bad idea, the fault must be hers. So she suffers the psychological and social consequences – self-blame, stigma or both.

The project 5-Minute Bedtime Stories resists this logic in a fabulous way. London-based artist Maria Gvardeitseva (divorced after 20 years of marriage, four children, numerous countries and shared challenges) takes a pronounced political and feminist approach to the story of her separation, which transforms grief, sorrow, and hatred in order to let them go. She offers artistic tools that help women to look at the situation with self-love, to rediscover the socio-political aspects of marriage and to cope with this life trauma and the challenges of patriarchy.

She does this in a surprising way – by reference to the fairy tales. In his structuralist masterpiece The Morphology of the Folk Tale Vladimir Propp described the typological similarity between a fairy tale and an initiation rite. The initiatory nature of marriage – to the secrets of sex (as used to be), childbirth, etc. – is not in doubt: the number of hallucinations and fantasies associated specifically with marriage and weddings in modern popular culture spills over.

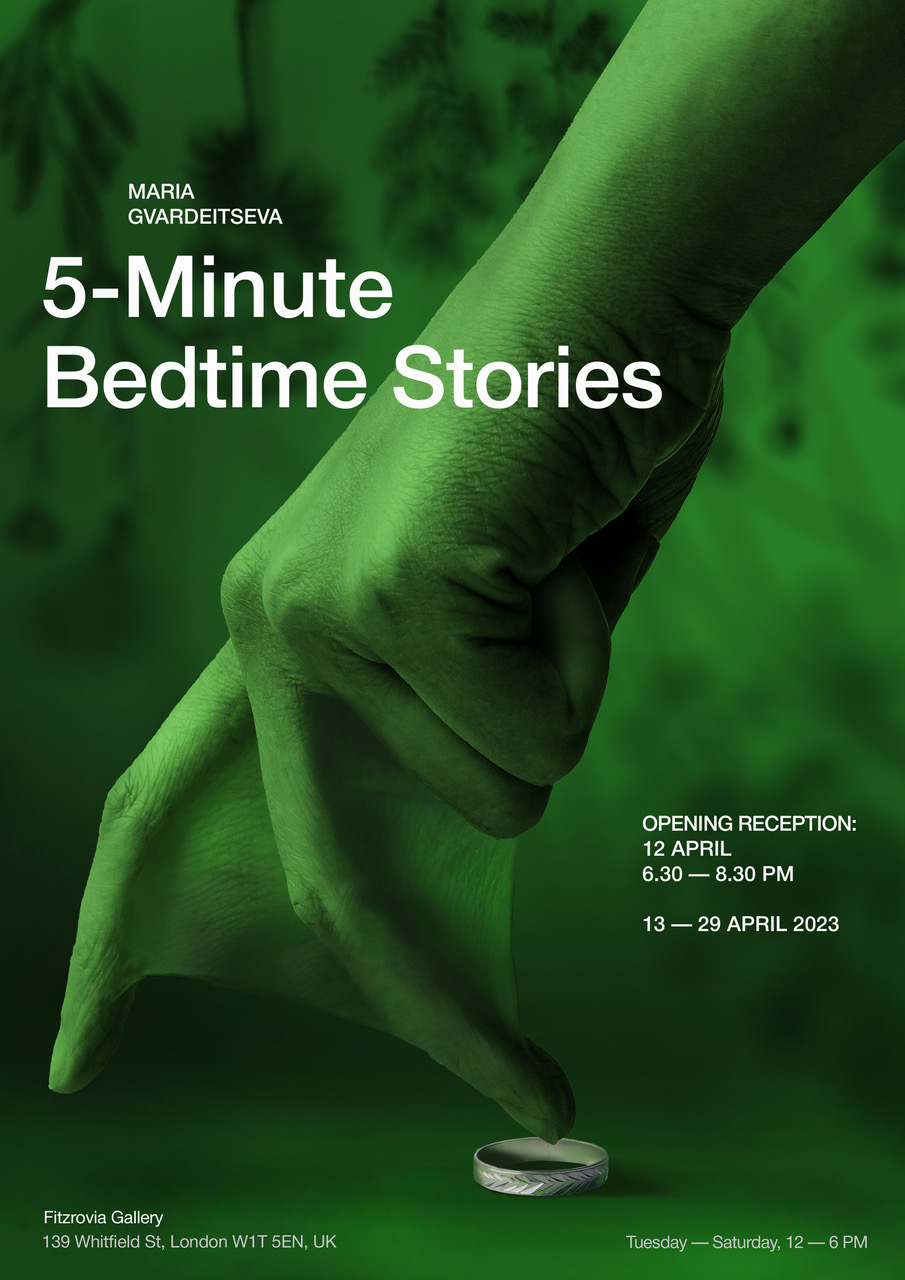

Think only of the diamond engagement ring. It is actually a marketing success of the ruthless De Beers diamond monopoly, and not a popular tradition: diamonds are rare because De Beers controlled supply and they are popular because the company backed huge marketing campaigns, which made diamond engagement rings de rigueur. The ring on a severed finger in Gvardeitseva’s installation emphasizes this irony.

But what particularly interests Gvardeitseva is Propp’s idea that, in the fairy tale, initiation of the hero to an adventure and a new status depends on stepping outside an institution and violating an interdiction. The hero – or heroine – is told “Don’t, on any account, go out of the yard!”. But they do go out, and then the impossible and wonderful happens.

If the only status imagined by our culture following divorce, the end of love or betrayal of a partner is drowning in a lake, retirement to a nunnery, or waiting for the next love-and-marriage opportunity, we perhaps need to think again about divorce and separation as an initiation and not always and inevitably as a tragedy.

The institution of marriage is less powerful now than it was in the past (in Slavic countries, almost within living memory, girls who died before marriage were buried in a wedding dress, as if to atone for a sin). No doubt there are reasons for that. However, women’s experience of divorce and separation in the role of victim or guilty party is worse than inexpedient.

Using the parallel with fairy-tales, Gvardeitseva suggests that violating an interdiction or stepping outside an institution can be a brave step with transformative consequences. Could there be fairy-tale divorce? Perhaps, at least, a more intense life in the self-revealed sense, initiation to a new stage, or maybe ultimate return to the same marriage institution in a more satisfactory form. A variety of possible “happily ever afters.”